In the interest of openly stating my biases, I thought I should mention the following before I continue. Neither have I heard nor read a discussion of Union Major General George Brinton McClellan without encountering an almost immediate treatise on his perceived faults. While not believing in his perfection as a field commander, I have always felt that his shortcomings received more emphasis than perhaps his service merited. I offer the following in that spirit.

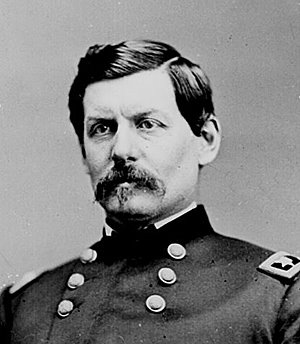

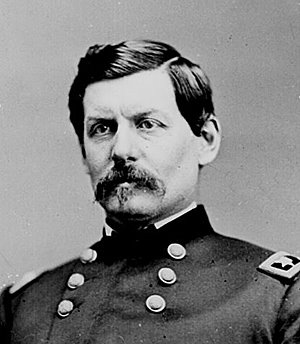

Major General George B. McClellan

Major General George B. McClellanIn late October 1862, President Lincoln continued to urge Major General George B. General McClellan to cross the Potomac and move on the enemy. Over a month had passed since the Battle of Antietam and Washington again grew impatient as the Army of the Potomac sat on the opposite side of its namesake’s river from the Confederate forces. To one of General McClellan’s reasons for not yet advancing, President Lincoln famously replied, "I have read your dispatch about sore-tongued and fatigued horses. Will you pardon me for asking what the horses of your army have done since the battle of Antietam that fatigues anything?"

In early October 1862, after Antietam and before the President sent his somewhat rhetorically flavored question, Confederate Cavalry Commander JEB Stuart had again ridden around the Army of the Potomac, as he had once previously on the Peninsula. Aware of this movement, McClellan sent the Union Cavalry in pursuit. Although unsuccessful in stopping Stuart, the bluecoats rode up into Pennsylvania through Hanover Junction and Gettysburg. On October 14, 1862, while reporting to General McClellan, Major General John E. Wool stated, "General Pleasonton, who was in pursuit of the rebel cavalry reports that they have been driven back, into Virginia, crossing the Potomac near the mouth of the Monocacy, and having marched 90 miles in the previous twenty-four hours, while Pleasonton, in pursuit, marched 78 miles in the same time." General McClellan wrote of this incident, " General Pleasonton ascertained, after his arrival at Mechanicstown, that the enemy were only about an hour ahead of him, beating a hasty retreat toward the mouth of the Monocacy. He pushed on vigorously, and near its mouth overtook them with a part of his force, having marched 78 miles in twenty-four hours, and having left many of his horses broken down upon the road." The Confederates, while at Chambersburg, also reportedly "supplied themselves on their route with 1,000 fresh horses" now unavailable to the Union Army.

General McClellan kept Washington informed of Stuart's raid and their pursuit. On October 12, he reported to General-in-Chief Henry Halleck, "The rebel cavalry under Stuart, which left Chambersburg yesterday morning in the direction of Gettysburg, reached the Potomac, near the mouth of the Monocacy, at about 9 a.m. to-day, having marched about 100 miles in twenty-four hours. General Stoneman, who was at Poolesville, near where the rebels passed, was ordered by telegraph, at 1 o'clock p.m. yesterday, to keep his cavalry well out on all the different approaches from the direction of Frederick, so as to give him time to mass his forces to resist their crossing into Virginia..." He would also report, "Six regiments of my cavalry had been sent to Cumberland to prevent the rebel depredations upon the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, which left us very deficient in cavalry here. As soon as Stuart's approach was known, however, one of these regiments was ordered back, but has not yet arrived."

On October 13, McClellan’s Chief-of-Staff (and Father-in-law) stated, "Governor Curtin reports that he has been informed that a force of rebels were within 8 miles of Concord, in Franklin Country, this morning, and that they stole 1,500 horses last night." Confederate General JEB Stuart would mention in his report to General Lee after the raid into Pennsylvania, " During the day a large number of horses of citizens were seized and brought along." and " We seized and brought over a large number of horses."

Given the above, the Government in Washington knew of the capture of horses available to the Union Army and of the activity of the Union Cavalry in pursuit of the Confederate forces. Multiple sources had also reported to Washington the concerns both with supplying remounts for the Army of the Potomac and with delivering supplies for their horses and mules. In mid-October, Union Quartermaster General Mongomery Meigs would write, "All the power of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad and of the Cumberland Valley Railroad has been used, under the direction of Brig.-Gen. Haupt, invested by the Secretary with special and full powers to do anything necessary to expedite the forwarding of supplies to the army under Gen. McClellan. It is nearly impossible to supply such an army, having over 30,000 animals to feed, by means limited to two railroads. The canal will be repaired and ready for use in a few days. It was hoped that water could have been admitted to it to-day. This, if boats can be found to navigate it, will increase the power of this department to forward supplies considerably. I understand, however, that everything called for has gone forward. What has been intercepted and destroyed by the rebel cavalry in rear of the army at Chambersburg and on the railroad I have not yet learned."

General Meigs would later in the month relay other concerns. "A case is reported in which horses remained fifty hours on the (railroad) cars without food or water, were taken out, issued, and put to immediate service. The horses were good when shipped, and a few days' rest and food would have recruited them, but the exigencies of the service, or perhaps carelessness and ignorance, put them to a test which no horses could bear."

After the Battle of Antietam, General McClellan would write, " This overwork had broken down the greater part of the horses; disease had appeared among them, and but a very small portion of our original cavalry force was fit for service. To such an extent had this arm become reduced, that when General Stuart made his raid into Pennsylvania on the 11th of October with 2,000 men, I could only mount 800 men to follow him."

Although not written until February 17, 1863, Chief Quartermaster Colonel Rufus Ingalls also discussed the condition of the army's horses after the Battle of Antietam in his official report.

"Immediately after the battle of Antietam, efforts were made to supply deficiencies in clothing and horses. Large requisitions were prepared and sent in. The artillery and cavalry required large numbers to cover losses sustained in battle, on the march, and by diseases. Both of these arms were deficient when they left Washington. A most violent and destructive disease made its appearance at this time, which put nearly 4,000 animals out of service. Horses reported perfectly well one day would be dead lame the next, and it was difficult to foresee where it would end or what number would cover the loss. They were attacked in the hoof and tongue. No one seemed able to account for the appearance of this disease. Animals kept at rest would recover in time, but could not be worked. I made application to send West and purchase horses at once, but it was refused on the ground that the outstanding contracts provided for enough; but they were not delivered sufficiently fast nor in sufficient numbers until late in October and early in November. I was authorized to buy 2,500 late in October, but the delivery was not completed until in November, after we had reached Warrenton."

The above by no means represents a comprehensive literature search concerning this one seemingly small issue. My intent in posting this includes noting that, although frequently quoted, the statement from President Lincoln questioning the condition of McClellan’s horses, and by inference the General himself, could include a brief statement or two concerning at least the partial legitimacy of his concerns. We may then view the oft-maligned General in perhaps a somewhat more sympathetic and debatably more accurate light.

Respectfully,

Randy

Please visit my primary site at

www.brotherswar.comAll original material Copyright © 2006. All Rights Reserved

Sources:

CivilWarHome.comOfficial Records – Ohio State UniversityUS National Park ServiceVirginia Center for Digital HistoryPhotographs from the National Archives & Records Administration and the Library of Congress respectively.

Fredericksburg's Reconstructed Stone Wall

Fredericksburg's Reconstructed Stone Wall

With the mention of 19th century moral courage, Abraham Lincoln easily comes to mind. His desire towards war's end to "let 'em up easy" certainly contradicted the fate many wished for the defeated Rebels. Had he lived, proposing this stance risked his own political harm as he sought to better the future of the Southerners in his care.

With the mention of 19th century moral courage, Abraham Lincoln easily comes to mind. His desire towards war's end to "let 'em up easy" certainly contradicted the fate many wished for the defeated Rebels. Had he lived, proposing this stance risked his own political harm as he sought to better the future of the Southerners in his care.